Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints: Palmer House (Block 9, Building 24), Williamsburg, Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Research Report Series - 1734

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2012

Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints

Palmer House

(Block 9, Building 24)

Williamsburg, Virginia

Table of Contents

| Purpose | 1 |

| Historical Background | 1 |

| Sampling Procedures | 2 |

| Sampling Locations | 2 |

| Results of Cross-Section Analysis | |

| Cornice | 3 |

| Rear Doorway | 12 |

| Mortar | 17 |

| Results of Binding Media Analysis with Fluorochrome Stains | 19 |

| Results of Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy | 25 |

| Results of Color Measurement | 28 |

| Conclusion | 31 |

| Appendix | |

| Sampling Memorandum | 33 |

| Cross-Section Preparation Procedures | 34 |

| Binding Media Analysis Procedures | 34 |

| Pigment Identification Procedures | 34 |

| Color Measurement Procedures | 35 |

| Color Measurement Data | 36 |

| Contact Sheets of Cross-Section Photomicrographs | 39 |

Cross-Section Microscopy Analysis of Exterior Paints

| Structure: | Palmer House, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation |

|---|---|

| Requested by: | Edward A. Chappell, Director, Architectural Research Department |

| Conservator: | Natasha K. Loeblich, Architectural Paint Analyst, Architectural Research Dept. |

| Consultant: | Susan L. Buck, Ph.D., Conservator and Paint Analyst |

| Date: | July 2007 |

Purpose

The goal of this project is to use cross-section microscopy to identify the early finishes, if they are present, in exterior paint samples from the Palmer House. For this research, finish samples were taken from the front and rear cornice, the rear doorway, and the brickwork. Samples were not taken from the cornice end boards on the west elevation as these did not appear to have a significant accumulation of paint when viewed from the ground.

Historical Background

Palmer House before restoration

Palmer House before restoration

A brick house existed on the site by 1738, but was completely rebuilt, possibly around 1754, after a disastrous fire. In 1857-58 a large brick wing was added onto the eastern end of the house as shown in the image below. This wing was removed in 1951-52 when the house was restored to its mid-eighteenth century appearance. An architectural report was written in 1956 on this restoration that gives details about which elements were replaced or changed.1 The report notes that the brick was cleaned with "steam and paint remover" since the "entire surface had been painted in later years." The painting may have been done to disguise the difference between the old bricks and the new bricks added in eastern wing. The architectural report indicates that the cornice on the front and rear elevations "with exception of a new crown mold is original and was patched only where necessary to replace rotted portions." According to the report, the cornice end boards on the west elevation are also original, as is the lower portion of the iron lightning rod. On the rear (south) elevation the door and trim were left in place with only a few repairs: "The original door and trim on south facade was fitted with a new sill to match the deteriorated original. The glazing in two upper panels of the door which was done in 1857 was removed and replaced by panels to match the original work. Except for the sill and the lintel of steel the doorway is original." All the windows of the house and the front door are new.

Sampling Procedures

Of the nineteen exterior samples examined in this report, fourteen were taken from the Palmer House by Edward Chappell on November 21, 2006 with a scalpel. Seven samples were taken from the rear cornice, five from the front cornice, and two samples were taken from the brickwork on the rear elevation. Four more samples were taken from the rear door by the author on June 27, 2007. All the samples were collected on-site in labeled bags and each was given a unique number corresponding to its recorded sample location. The exact sample locations are provided in the following table.

Sampling Locations

| Location | |

|---|---|

| JP1 | Rear cornice, bottom edge of horizontal bed molding, adjoining lower fascia, below 13th modillion from west end |

| JP2 | Rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west end |

| JP3 | Rear cornice, bed molding, bottom cyma, lower vertical edge, 3" right of 14th modillion from west end |

| JP4 | Rear cornice, outer edge of fillet, between cyma and ovolo of bed molding, under 12th modillion from west end |

| JP5 | Rear cornice, between 13th and 14th modillion from west end, outer, lower edge of fillet, at top of bed molding |

| JP6 | Rear cornice, outer, lower edge of fillet between cyma and ovolo of bed molding, east of joint between the 15th and 16th modillion from west end |

| JP7 | Rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion from west end |

| JP8 | Front cornice, 15th modillion from west end, lower edge of west side, 3" back from front |

| JP9 | Front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front |

| JP10 | Front cornice, bottom outer edge of lower cyma on bed molding, below 2nd modillion from west end |

| JP11 | Front cornice, 2nd modillion from west end, face of fillet on cymatium, 4½" back from front edge |

| JP12 | Front cornice, upper outer edge of fillet at top of bed molding below 2nd modillion |

| JP13 | Front cornice, patch of bed molding at west end, middle fillet |

| JP14 | Rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave |

| JP15 | Rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge of architrave |

| JP16 | Rear door, left architrave, in join of outer and center molding, ~4' up |

| JP17 | Rear door, left architrave, in join of center and inner molding, ~2½' up |

| JP18 | Rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down |

| JP19 | Rear door, left top of bead around bottom left raised panel |

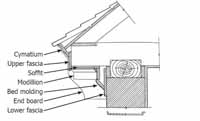

Detail of Palmer House Cornice1

Detail of Palmer House Cornice1

Results of Cross-section Analysis

Samples from the front and rear cornice have a similar extended finish histories that suggest that they may be original elements. The first five generations of paint are all cream-colored. However, there is an unusual brown layer in generation six of the rear cornice that can be used to compare the stratigraphies. A table with the comparative finish histories of the front and rear cornice is included on page eleven of this report.

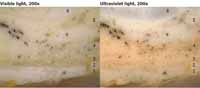

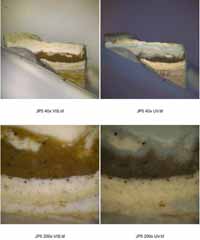

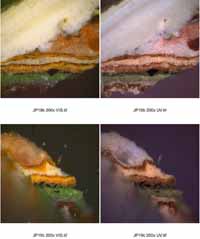

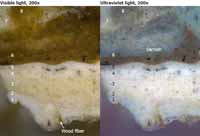

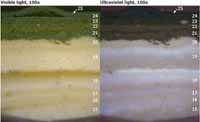

The cross-section from the rear cornice shown below indicates that a resinous sealant was applied to the wood before painting. The resinous sealant was found in virtually all samples when wood substrate was present. The resin has an orange fluorescence in reflected ultraviolet light that is characteristic of shellac. At the top of the sample are fragments of the cream-colored paint of generation one.

Sample JP7, rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion

from west end

Sample JP7, rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion

from west end

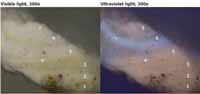

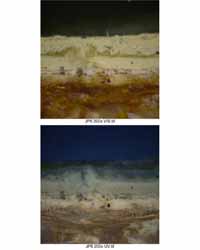

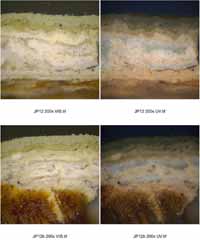

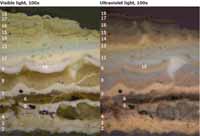

Sample JP2 from the bed molding of the rear cornice has the most complete stratigraphy of the cornice samples. This is not surprising as it was taken from an area that would have been protected from wear and weathering. There are at least eighteen generations of finish. The first five generations are cream-colored paints with some autofluorescence. Generation six is a dark brown paint with a brown varnish above it. Binding media analysis with fluorochrome stains suggests that this layer contains zinc, probably present as the pigment zinc white that would date the layer to 1845 or after (see page twenty-two)1. Generation seven is a cream-colored paint similar to the earlier generations of paint. Generation eight is a resinous, light brown paint that is visible only on the far right of these cross-sections. Generations nine, ten, and eleven are finely ground white paints that have a sparkly appearance in ultraviolet light that suggests the presence of zinc white pigment. These layers also appear to have a bluish fluorescent varnish coat that was probably applied before the paint was fully dried. Generation twelve consists of a cream-colored primer and a light blue paint. There is no visible separation between these layers so they were probably applied at the same time and both of these paints have a bluish autofluorescence. Generation thirteen consists of a light green primer and a cream-colored paint. As with the previous generation, there is no separation between these layers. Generation fourteen, fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, and eighteen are tan paints with dark autofluorescence and probably have synthetic binders. It is possible to see from this cross-section that the last two modern paints are identical in color and that this color is significantly darker and more green than the early cream-colored paint layers. The 1956 architectural report on this house specifies that all trim besides the basement window sash and the doors be painted "stone gray #271" as "usual". Unfortunately, there is no indication which manufacturer made this paint. Perhaps generation fourteen or fifteen represents the first application of "stone gray #271".

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

The cross-section below from the rear cornice begins with the cream-colored paint of generation one. The wood substrate is missing from this cross-section, but there is a wood fiber trapped in the first paint layer indicating that this is indeed the first finish. An upper layer of modern paint with bluish fluorescence flowed down a crack and can be found below the first generation. This layer reacted very differently from the early layers when fluorochrome stains were applied for the purpose of binding media analysis (see page twenty). There is a slight collection of grime between each of the earliest layers so they were not applied at the same time, but allowed to weather somewhat before the next layer was applied. Generation three in most samples is thicker than the other early layers and slightly more coarse. The first four paint layers reacted weakly for oils when stained with fluorochrome stains. Generation five reacted more strongly for oils (see page twenty). This suggests that these layers are traditional oil-bound paints. An oil component in the binding media normally quenches fluorescence so the bright autofluorescence of these layers in reflected ultraviolet light suggests they may contain lead white pigment which has a whitish autofluorescence. Generation six is an unusual coarse brown paint that has muted fluorescence. This layer reacted positively for oils when stained, and an oil binder, as well as the absence of naturally autofluorescent pigments, could account for the muted fluorescence of this layer. Above the brown paint is a thick varnish layer. When the varnish was applied it may have picked up some of the pigments from the surface of the brown layer, but it also appears to have some translucent chalk particles suspended in it. This is indicative of a flatted varnish that has fillers added to reduce its gloss. The varnish has a bluish fluorescence in ultraviolet light that suggests a synthetic resinous component. It appears that some of the light brown paint from generation eight has flowed down under generation seven through cracks, and it may be contributing to the bluish autofluorescence of generation six.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

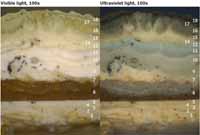

Another cross-section from sample JP2 is shown below that provides better images of the light brown paint in generation eight. The upper half of this generation is translucent and may have had a flatted varnish applied while the paint was still wet. Examination of uncast samples indicates that this is an opaque paint and not just a very thick pigmented varnish. The varnish in the upper part of the layer has a more bluish fluorescence than the paint below it. In this sample, generation eight is separated from the brown paint of generation six by the cream-colored paint of generation seven. The light brown paint of generation eight is not found in other samples from cornice, however, in some samples from the rear cornice there appears to be layers in the brown paint of generation six with pockets of light brown material. It may be that the light brown paint in generation eight has flowed down into generation six. More sampling will be needed before this layer can be fully identified since it appears that only one sample from the rear cornice has a full stratigraphy.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

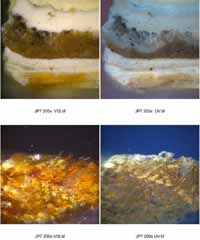

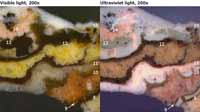

Other samples from the rear cornice have a similar stratigraphy to sample JP2 but are missing the later light brown, blue, and green paint layers. The cross-section below from sample JP7 was taken from the lower fascia of the rear cornice. It is representative of all the samples from the rear cornice with the exception of sample JP2 and it has a nearly complete stratigraphy. Like most samples from the rear cornice the cross-section is missing the light brown paint of generation eight and the blue finish coat of generation twelve, though it does have the generation twelve cream-colored primer. This sample, like other samples from the rear cornice, is also missing generation thirteen which consists of a green primer and a cream-colored finish coat. The fact that certain colored layers are found only in cross-sections from sample JP2 might suggest a polychrome scheme where some elements were picked out in contrasting colors. However, JP2 was taken from the bed molding on the rear cornice, as were samples JP1, JP3, JP4, and JP6 all of which also have no evidence of the light brown, blue, or green paint.

This cross-section from JP7 shown below also has layers in generation six that may be material from the light brown paint of generation eight that flowed down into this layer or generation six may have been applied in multiple coats. There is no evidence of grime between the layers so all the coats were probably applied at roughly the same time.

Sample JP7, rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion from west end

Sample JP7, rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion from west end

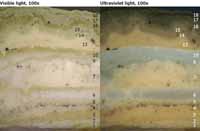

The front cornice has a slightly different stratigraphy than the rear cornice, and a table with the comparative stratigraphies of the front and rear cornice can be found on page eleven. The first five generations of cream-colored paint appear to be identical to those found on the rear cornice. However, there is no evidence of the brown paint that was applied in generation six to the rear cornice. Instead, a somewhat translucent cream-colored paint was applied to the cornice on the front of the building in generation six. This layer appears to have a bluish fluorescent varnish that was applied before the paint below it fully dried. Generations seven is the same cream-colored paint on both elevations. There is no evidence of the light brown paint found in generation eight in sample JP2 from the rear cornice, instead the front cornice is cream-colored in this period. Generations nine and ten are identical cream-colored paints on both cornices, though generation ten is missing from this particular cross-section. As found on the rear cornice, there appears to be bluish fluorescent varnishes above the paints in these layers. There is grime and mold accumulation above generation nine in the cross-section below that suggests this layer was exposed for a long period of time. Generation eleven, a cream-colored paint, and generation twelve, a blue paint over a cream-colored primer, are missing from the front cornice. On the rear cornice generation thirteen is a cream-colored paint that in sample JP2 was found to have a green primer This generation is present on some samples from the front cornice and consists of a cream-colored paint with no primer. Generations fourteen through eighteen are identical on both cornices.

Sample JP9, front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front

Sample JP9, front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front

Interestingly, there is a brown material at the bottom of this cross-section from the front cornice that is very disrupted. This brown material is only found in cross-sections from sample JP9. The small amount of material makes it very hard to classify. It could be a degraded translucent coating with embedded grime, but it is not possible to be sure.

This cross-section shows significant grime and mold accumulation on top of generation four.

Sample JP9, front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front

Sample JP9, front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front

The cross-sections below are also from the cornice on the front elevation and show the finish history in more detail. Again, generations eleven and twelve on the rear cornice are missing from the front cornice even though there is very little grime accumulation above generation ten on this sample. This cross-section shows a varnish coat above generations six and ten.

Sample JP10, front cornice, bottom outer edge of lower cyma on bed molding, below 2nd modillion from west end

Sample JP10, front cornice, bottom outer edge of lower cyma on bed molding, below 2nd modillion from west end

A table with the comparative finish histories of the front and rear cornice is included below. Note that in one sample from the front cornice there was evidence of a brown material below the first paint layer. There was too little evidence to be sure of what the material was, although it appears to be a pigmented coating. Generations one through five are identical on both cornices. Generation six is white on the front cornice and dark brown on the rear cornice. Generation eight, a light brown paint, is missing from the front cornice. Generations eleven and twelve on the rear cornice are not found on the front cornice and the green primer found in one sample from the rear cornice is not found on the front cornice.

| Front Cornice | Rear Cornice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generation | Visible light appearance | Ultraviolet light appearance | Visible light appearance | Ultraviolet light appearance |

| 18 | Tan | Dark | Tan | Dark |

| 17 | Tan | Dark | Tan | Dark |

| 16 | Tan | Dark | Tan | Dark |

| 15 | Tan | Muted tan | Tan | Muted tan |

| 14 | Tan | Muted tan | Tan | Muted tan |

| 13 | Cream | Bright | Green primer, cream finish coat | Bright |

| 12 | - | - | Cream primer, blue finish coat | Blue |

| 11 | - | - | Cream finish coat, varnish | Muted blue |

| 10 | Cream finish coat, varnish | Muted pink | Cream finish coat, varnish | Muted pink |

| 9 | Cream finish coat, varnish | Muted green | Cream finish coat, varnish | Muted green |

| 8 | - | - | Light Brown | Pink/blue |

| 7 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| 6 | White finish coat, varnish | Bright, bluish | Brown finish coat, varnish | Dark, bluish |

| 5 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| 4 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| 3 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| 2 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| 1 | Cream | Bright | Cream | Bright |

| ΔE | Brown | Dark | - | - |

| Resin sealant | Muted orange | Resin sealant | Muted orange | |

| Wood | Wood |

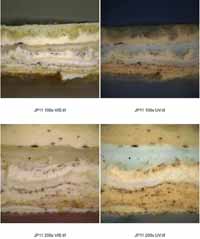

Two samples taken from the rear door architrave indicate that it has an identical finish history to that of the cornice on the front elevation (see page ten) and both elements have eighteen generations of finish. Like the cornice, the first generation of finish on both samples from the door architrave is a cream-colored paint with a pinkish autofluorescence. The layer does not appear to contain colored pigments but does have colored particles embedded in its upper surface that are most likely contaminants. If the brickwork originally had a chalky red limewash, some pigmentation from that could have washed down onto the trim. Interestingly, there is no evidence of the brown paint found in generation six in the rear elevation cornice samples.

Sample JP16, rear door, left architrave, in join of outer and center molding, ~4' up

Sample JP16, rear door, left architrave, in join of outer and center molding, ~4' up

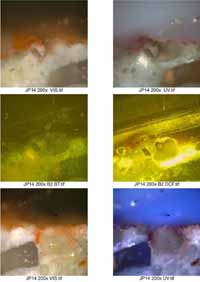

The back door of the Palmer house on the south elevation appears to be an original element and has at least twenty-five generations of finish, including many faux graining schemes. This is several more generations than found on the woodwork, which suggests that the door was painted more often because it was more accessible or to hide wear. The first generation of finish consists of a cream-colored primer and a worn dark red-brown finish layer. In generation two a dark red-brown primer and finish coat were applied. Generation three consists of a bright green paint with a gray primer. The top of this layer is dark in ultraviolet light and may have an oil varnish or glaze. The next generation is another green paint that probably has a resin component since it has more autofluorescence. Generation five is a third green paint that has less fluorescence along the top of the layer and may have a oil varnish or glaze. Generation six is a decorative scheme that is probably the first the faux graining system. It consists of a thin orange primer, (this is best seen where it flowed into a crack in the green paint below it on the left side of the cross-section), a yellow base coat, a red glaze, and an unpigmented varnish. This varnish almost wore away and it is not visible in this cross-section, however, in generation seven a second varnish was applied to refresh the faux graining. Both varnishes probably have resinous components based on their autofluorescence in ultraviolet light. Generation eight may be a second faux graining scheme with a cream-colored base coat, red glaze, and a thick pigmented varnish with a resinous component. This varnish cracked with age and has evidence of mold growth. Generation nine is composed of an orange paint with a thin resinous varnish that flowed into the cracks in the varnish of the generation below. Generation ten consists of a pink primer containing zinc white (see page twenty-three), a pink base coat, a brown glaze possibly with a resinous component, and a clear resinous varnish. The varnish appears to have contracted either from heat or exposure or both giving it a globular appearance in cross-section. Generation eleven appears to be a graining scheme with a cream-colored base coat and brown varnish that is non-fluorescent, probably due to an oil component in the binder. This finish was replaced in generation twelve with a graining system composed of a yellow base coat, a brown oil glaze (based on its lack of fluorescence), and an unpigmented varnish not visible in this cross-section. In generation thirteen, this finish was renewed with a pigmented varnish. Lastly, a worn graining scheme was applied with a pink base coat, brown glaze, and pigmented varnish in generation fourteen. The upper finish layers are discussed on the nest page and the full finish history of the door is presented in table form on page fifteen.

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

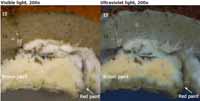

After the last graining scheme of generation fourteen it appears that the door was sanded to remove loose paint. Evidence of this can be found in the lower set of cross-sections which have a disrupted stratigraphy above generation fourteen. After the sanding, six generations of cream-colored paint were applied, that appear identical to those applied to the cornice and door architrave in generations eight through eighteen. Generations twenty-one through twenty-five on the door, however, are modern green paints not found on the other woodwork. All the green paints are roughly the same color and are similar to the early green paints in generations three, four, and five. This may be evidence of early paint analysis. If the analysis was done by scraping or sanding away later layers it is not surprising that the first two dark red-brown paint generations were missed or assumed to be primers.

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Sample JP19, rear door, left top of bead around bottom left raised panel

Sample JP19, rear door, left top of bead around bottom left raised panel

The cross-sections on this page show generation one through fourteen at higher magnification, making it easier to see the varnish and glazing layers.

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

The following table gives the finish history of the original rear door as it compares to the generations of finish on the door architrave and front cornice. The door was often repainted even when the other woodwork was not so the numbering of the generations is different. The tenth generation on the door and the sixth generation on the architrave and the cornice are the first generations to contain the pigment zinc white, so these generations must date to 1845 or after.

| Generation | Door | Architrave & Front Cornice | Generation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21-25 | Greens | Tans | 14-18 |

| 15-20 | Creams | Creams | 8-13 |

| 14 | Pink base coat, brown glaze, pigmented varnish | (not repainted) | - |

| 13 | Pigmented varnish | (not repainted) | - |

| 12 | Yellow base coat, brown glaze, brown varnish | (not repainted) | - |

| 11 | Cream base coat, brown finish coat | Cream | 7 |

| 10 (dates to 1845 or after) | Pink primer, pink base coat, brown glaze, varnish | Cream | 6 (dates to 1845 or after) |

| 9 | Orange, thin varnish | Cream | 5 |

| 8 | Cream base coat, red glaze, pigmented varnish | Cream | 4 |

| 7 | Varnish | (not repainted) | - |

| 6 | Orange primer, yellow base coat, red glaze, varnish | Cream | 3 |

| 5 | Green | (not repainted) | - |

| 4 | Green | (not repainted) | - |

| 3 | Gray primer, green finish coat | Cream | 2 |

| 2 | Dark red-brown primer and finish coat | (not repainted) | - |

| 1 | Cream primer, dark redbrown finish coat | Cream | 1 |

| Wood with resin sealant | Wood with resin sealant |

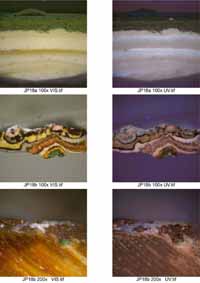

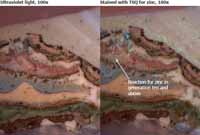

Two samples were taken from the mortar on the rear elevation from areas that appeared to have evidence of a red coating. All the coatings on this brickwork are somewhat suspect as the 1956 architectural restoration report noted that the brick was cleaned with "steam and paint remover" and that the "entire surface had been painted in later years." Thus any coatings found on the brick surface could likely be residues of later painting. It is also possible that any later painting that survived the cleaning may have protected original limewash from exposure and preserved it. The cross-sections shown below do have evidence of modern paints. The first finish is a thick, opaque red paint with reddish autofluorescence that reacted positively for oils when marked with fluorochrome stains. It is not clear when this paint was applied. The next layer is a brown paint that may correspond to the brown paint in generation six on the rear cornice. This is followed by two cream-colored paints with bright autofluorescence, and a final cracked tan paint with dark autofluorescence. These last three layers appear to correspond to generations eleven, fourteen, and fifteen in samples from the rear cornice.

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

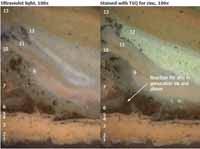

Other cross-sections from the mortar show evidence of what may be a worn red-pigmented limewash. This material remains mostly where it flowed into crevices in the mortar. The fact that the mortar has such an uneven surface could suggest that it was worn down before this coating was applied. However, there is no evidence of grime trapped between the mortar and supposed limewash which would indicated that the mortar was exposed for some time without a coating. It is also possible that this material is an early limewash that survives only where it flowed into natural crevices in the mortar substrate and was protected from wear.

Unlike the red paint shown on the previous page, this material is translucent and has a muted fluorescence typical of a limewash. Unfortunately, there is nothing in this layer the can help date it so it is not possible to determine when it was applied. However, it was applied before all the paint layers shown in the cross-sections on the previous page.

When the fluorochrome stain DCF was applied, the supposed limewash layer seems to have reacted positively for oils, which suggests that it might be a oil paint (see page twenty-four). However, the stain tends to soak into the porous mortar substrate, yielding a false positive there, and this may be the same type of reaction observed in the possibly chalky limewash.

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

Sample JP15 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge of architrave

Sample JP15 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge of architrave

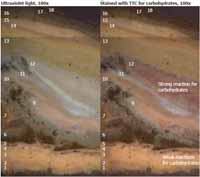

Results of Binding Media Analysis with Fluorochrome Stains

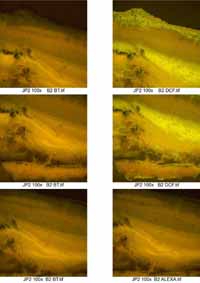

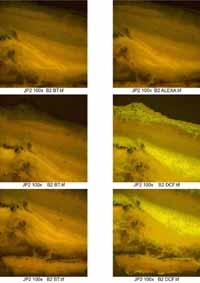

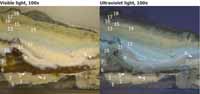

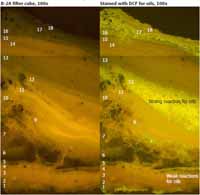

Samples from the cornice and the mortar were selected for staining with biological fluorochrome stains that mark out proteins, carbohydrates, oils, and zinc (Zn2+) in the layers. Sample JP2 from the rear cornice is shown below and has evidence of the brown, light brown, blue, and green paint found in generations six, eight, twelve, and thirteen respectively. There was no noticeable reaction in the early layers for proteins. There were very weak reactions for carbohydrates in many of the layers, including the first five cream-colored paint generations, as shown by a reddish-brown positive reaction color. The carbohydrates detected by the fluorochrome stain TTC may be natural gums mixed into the paint binder either as a wetting agent or to help grind the pigments. There were strong reactions for carbohydrates in the brown paint of generation six and the cream-colored primer and blue paint of generation twelve.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

There were reactions for oils in nearly every layer in sample JP2 when the fluorochrome stain DCF was applied. There is a bright yellow reaction color at the very bottom of the sample from a modern paint that flowed down a crack from above. Generations one, two, and three turned slightly pink when the stain was applied, suggesting the presence of saturated lipids in these early cream-colored paints. This type of reaction is appropriate for aged oil paints. Generation four has a weak reaction and generation five a strong reaction for unsaturated lipids, indicated by a bright yellow reaction color. Most layers above this reacted at least weakly for unsaturated lipids, as appropriate for less aged oil paints. Especially strong reactions were found in generations twelve, sixteen, seventeen, and eighteen, which is common for modern oil-based paints.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

The cross-section below also shows reactions for oils with the stain DCF at a different wavelength of ultraviolet light. The pink reaction color of the earliest cream-colored paints is slightly more noticeable here and suggests the presence of saturated lipids. This reaction consistent with an aged oil paint. There is a bright reaction color at the very bottom of the sample from a modern paint that flowed down a crack from above.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

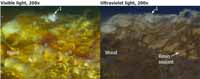

There were positive reactions for zinc (Zn2+) beginning in the dark brown paint of generation six, as shown by a bright blue reaction color. Since a feasible commercial method for delivering zinc white pigment in oil paint was not developed until 1845, generation six must postdate this. There is a bright reaction color at the very bottom of the sample from a modern paint that flowed down a crack from above.

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Sample JP2, rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west

Stained with TSQ for zinc, 100x

Stained with TSQ for zinc, 100x

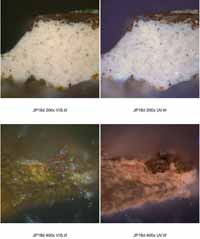

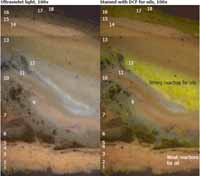

A sample from the door was stained with the fluorochrome stain TSQ to mark the presence of zinc (Zn2+). The first layer to react positively for zinc was the pink primer of generation ten. Some layers in upper generations also reacted positively, especially the upper cream-colored paint layers. On the right side of the cross-section below, the zinc white containing paint of generation eleven flowed down a crack. This cross-section was also stained with DCF to mark out the presence of saturated and unsaturated lipids, but the reactions were too weak to be useful.

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Sample JP18, rear door, left side of left middle raised panel, 1" down

Cross-sections from the mortar were stained to see if there was any evidence of oils in the early generations. The red paint stained strongly for oils as shown by a bright yellow reaction color. The stain also soaked into the porous substrate yielding a false positive in the mortar though this could also represent the oil binder of the paint soaking into the substrate.

Sample JP15 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge of architrave

Sample JP15 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge of architrave

One of the samples that appears to have evidence of a red limewash was stained with the fluorochrome stain DCF as well. The supposed limewash seems to have stained in a spotty reaction for oils, but this may be a false positive as the mortar also seems to have absorbed some of the stain.

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

Sample JP14 from rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle of architrave

Results of Pigment Identification with Polarized Light Microscopy

Polarized light microscopy was used to identify the pigment composition of dispersed pigments from the earliest cream-colored layers on the cornice. Two layers were selected for examination: the first layer in sample JP4 from the rear cornice, and the first layer from sample JP10 from the front cornice. No colored pigment particles were found in either of the early paint layers. Instead, there was only lead white pigment, and other colorless paint fillers such as chalk. This suggests that the current slightly darkened color of the early paints is caused by the degradation and darkening of the oil binder and not by the addition of colored pigment particles.

JP4 dispersed pigment particles

JP4 dispersed pigment particles

JP10 dispersed pigment particles

JP10 dispersed pigment particles

Dispersed pigments from the earliest cream-colored layer on the door architrave were examined with polarized light microscopy to see how that layer compares with the paint on the cornice. The first paint layer was isolated from uncast portions from sample JP16 and JP17. The majority of the pigment composition in both samples is lead white, however, some red and yellow ochre pigments were found in both samples. It is not clear if these are intentional pigmentation or contaminants. In the cross-sections the colored pigments are not evenly dispersed throughout the layer, but lie along the boundaries. Likewise, in the dispersed pigment samples the colored pigments often remain in discrete clumps not fully dispersed among the lead white. In the upper photomicrographs shown below, the red and yellow ochre pigments are associated with a clump of dirt or grime, while the rest of the sample area contains only lead white. It seems likely that the first generation paint on the door architrave was composed of lead white alone, as found on the cornice, and that the colored pigment particles are some kind of contaminant.

JP16 dispersed pigment particles

JP16 dispersed pigment particles

JP17 dispersed pigment particles

JP17 dispersed pigment particles

A dispersed pigment sample from the dark red-brown paint from the first generation on the rear door was examined with polarized light microscopy as well. The paint was isolated from uncast portions of sample JP18. A variety of pigments were found in this paint including red and yellow ochres, lampblack, and lead white. Many of the pigments are fairly large, indicating that the paint was coarsely-ground, which is consistent with the supposed early date of the paint.

Results of Color Measurement

Color measurements were undertaken for this report from samples from the cornice, and the rear door and architrave. Two uncast chips of material from sample JP4 from the rear cornice and from two uncast chips from sample JP10 from the front cornice were selected and in both samples the first cream-colored paint layer was measured. Twelve color measurements were taken, three from each uncast sample. The average measurements from the first layer on the front and rear cornice are different from each other by a ΔE (Delta E) value of only 0.99. Generally, ΔE values below 2 are indicate a color difference that is hard for the human eye to differentiate. Thus, it seems likely that the first-generation color on the front and rear cornice is identical.

The closest actual measurement to the average color value of all samples from the cornice was taken from an uncast chip from sample JP4 and it had an L* value of 73.29, an a* value of -1.15, and a b* value of +12.53, which is different from the average by a ΔE value of only 0.38. The best commercial match found to this measurement is Sherwin Williams 2065 "Windsor Greige" which has an L* value of 74.44, an a* value of -0.28, and a b* value of +13.79. This commercial paint color is different from the color of the first generation of paint in sample JP4 by a ΔE value of 1.91. Thus this commercial paint match could be used for reproducing the aged, degraded color of the first-generation paint applied to both the front and rear cornice.

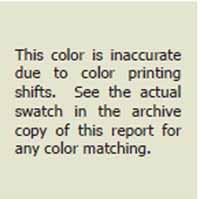

Sherwin Williams 2065, best commercial match to aged, original cornice paint

Sherwin Williams 2065, best commercial match to aged, original cornice paint

After exposing the samples to sunlight in a window for three weeks, the first-generation paint on the cornice had changed by a ΔE value of 3.67, becoming less yellow. All the measurements from the lightbleached samples were averaged and the closest measurement to the average was from sample JP4. That sample had an L* value of 74.33, an a* value of -0.55, and a b* value of +8.77. The best commercial paint match for the light-bleached, first generation paint on the cornice is Sherwin Williams DMV 120 'Watermark" from the Mount Vernon Estate Colors Collection. This paint has an L* value of 75.51, an a* value of -1.97, and a b* value of +9.68 which is different from the light-bleached paint on the cornice by a ΔE value of only 2.06.

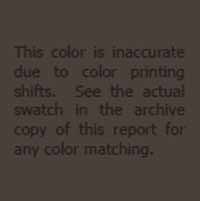

Sherwin Williams DMV 120, best commercial match to light-bleached original cornice paint

Sherwin Williams DMV 120, best commercial match to light-bleached original cornice paint

Seven fragments from uncast material from samples JP16 and JP17 from the rear door architrave were chosen for color matching. The first layer of paint was isolated and eight measurements were taken. The measurement values were averaged and the closest measurement to the average from sample JP17 had an L* value of 74.80, an a* value of -0.23, and a b* value of +17.93. The best commercial match to the degraded and aged paint on the rear door architrave is Sherwin Williams 6142 "Macadamia" which has an L* value of 76.37, an a* value of -0.19, and a b* value of +17.43. This commercial paint is different from the first generation of paint on the door architrave by a ΔE value of 1.65. Thus this commercial paint match could be used for reproducing the aged, degraded color of the first generation of paint applied to the door architrave.

Sherwin Williams 6142, best commercial match to aged, original door architrave paint

Sherwin Williams 6142, best commercial match to aged, original door architrave paint

After exposing the samples to sunlight in a window for three weeks, the first-generation paint on the door architrave had changed by a ΔE value of 6.00 becoming less yellow. All the measurements from the light-bleached samples were averaged and the closest measurement to the average was from sample JP17. This sample had an L* value of 74.90, an a* value of +0.17, and a b* value of +11.79. The best commercial paint match for the light-bleached, first generation paint on the cornice is Sherwin Williams DCL 033 "Clapboard" from the Carolina Lowcountry Collection. This paint has an L* value of 75.57, an a* value of -0.28, and a b* value of +11.63, which is different from the light-bleached paint on the cornice by a ΔE value of only 0.82.

Sherwin Williams DCL033, best commercial match to light-bleached original door architrave paint

Sherwin Williams DCL033, best commercial match to light-bleached original door architrave paint

Before light bleaching the color measurement of the first-generation paint on the door architrave was found to have a color value different from the first paint on the cornice by a ΔE value of 5.86 and after light bleaching it was different by a ΔE value of 2.21. These values are just high enough that it is possible to differentiate by eye between the first paints on the cornice and door architrave. However, both first-generation paints are similar shades of tan and the difference in color could be explained by the fact that early paints were often not well mixed and the color is somewhat variable. The different colors might also be explained by differences in aging and weathering of the paint due to their different locations on the building. When the dispersed pigment samples were examined with polarized light microscopy there were some pockets of colored pigments in the first paint layer on the door architrave. These, however, seem to be contaminants and not intentional pigmentation. The fact that the first-generation paint on both the cornice and door architrave is fairly similar in color supports the theory that these two paints are, in fact, identical and that the pigmentation is not intentional.

30While the commercial paint matches provided on the previous page could be used to reproduce the degraded or light-bleached appearance of the first generations of paint on the cornice and door architrave, it is more likely that none of the colors are fully indicative of the original appearance of the building in the eighteenth century. Since the first generation paint on both the cornice and door architrave is thought to be colored only with lead white pigment its color even after light bleaching is probably due to embedded grime and darkening of the oil binder with age. So it might be more accurate to repaint the trim with a color representative of fresh lead white in linseed oil. A fresh paint composed of lead white in linseed oil would certainly originally have been much lighter, though not as bright as a modern "cool" white. A batch of lead white in linseed oil paint prepared by Susan Buck in 2004 and applied to a shellacked pine board was measured at that time to have a color value of L* 91.07, a* -1.26, b* +11.29. A good commercial paint match to this is Martin Senour CW 707 "Bracken Cream Medium White" from the Williamsburg Color Collection. This paint has a value of L* 90.40, a* -1.60, b* +10.60, which is different from the fresh lead white in linseed oil paint by a low ΔE value of only 1.02. Hence, this commercial paint match could be used for reproducing a fresh lead white in linseed oil paint, which is what the evidence suggests was the first generation of paint originally applied to the cornice, door architrave, and probably all the trim.

Martin Senour CW707, best commercial match to fresh lead white in linseed oil

Martin Senour CW707, best commercial match to fresh lead white in linseed oil

The most recent modern paint on the trim was also measured. It was found to have an L* value of 57.98, an a* value of -0.75, and a b* value of +16.08, which is different from the measurement of the first-generation degraded paint on the cornice by a significant ΔE value of 15.72, and from the door architrave by a ΔE value of 16.93. (The current paint is much darker and slightly more blue than both original paints.) Thus, the current paint is a very bad match for either the aged original paint or for fresh lead white in linseed oil paint and is not a good interpretation of the original appearance of the Palmer House.

A final color measurement was made of the dark red-brown paint in the first generation on the rear door. Six measurements were taken from uncast fragments from sample JP18 from the door and averaged. The closest measurement to the average had a color value of L* 27.81, a* +3.89, and b* +6.58. A good commercial match for this is Benjamin Moore 2115-10 "Appalachian Brown", which has a value of L* 28.48, a* +3.53, and b* +5.92. This is different from aged, original paint by a low ΔE value of only 1.01 so this commercial match would be a good color to use for replication.

Benjamin Moore 2115-10, best commercial match to aged, original door paint

Benjamin Moore 2115-10, best commercial match to aged, original door paint

After light bleaching for three weeks with sunlight, the first-generation paint on the door had changed by a ΔE value of 0.55, becoming slightly less yellow. All the measurements from the light-bleached samples were averaged and the closest measurement to the average was from sample JP18. This sample had an L* value of 27.95, an a* value of +4.45, and a b* value of +6.22. The best commercial match for the light-bleached paint is still Benjamin Moore 2115-10 "Appalachian Brown", as shown on the previous page. This paint is different from the light bleached first generation door paint by a ΔE value of 1.10.

Conclusion

Analysis of the samples collected from the Palmer House indicates that there is still evidence of original paint on the front and rear cornice and the rear doorway. The extended finish history of all of these elements confirms that original elements remain despite alterations and restoration.

Cross-section microscopy analysis suggests that the first five generations on both the front and rear cornice and the door architrave are cream-colored paints. These layers are likely to be oil-bound paints as the application of fluorochrome stains suggest that saturated and unsaturated lipids are present in these layers. The first generation of paint on both the front and rear cornice was found to contain lead white and no other colored pigments and yielded very similar color measurements, suggesting that the same paint was originally applied on both elevations. The first-generation paint on the door architrave was found to have some colored pigments, based on polarized light microscopy pigment analysis, but these seem to be contaminants. It is possible that rain washed down some pigments from a colored limewash applied to the brickwork, though this cannot be proved. It is also possible that the colored pigments are from the soil on the site since red and yellow ochre both occur naturally in the reddish soil surrounding the site. It seems most likely that the first-generation paint on the door architrave was the same cream-colored paint applied to the cornice originally, and that it was pigmented only with lead white. The evidence from the cornice and door architrave can be extrapolated to suggest that all the trim on the building was cream-colored for the first five generations at least. This is especially useful since the windows and front doorway have been replaced.

Throughout most of its lifetime the cornice was painted with cream-colored paints similar to the door architrave, though there are a few exceptions to this. In generation six a dark brown paint was applied only to the rear cornice. This paint was found to contain zinc white pigment dating it to 1845 or after. One sample from the rear cornice also had evidence of a light brown paint in generation eight, a blue finish coat in generation twelve, and a green primer in generation thirteen. These colored paints were not found in any other sample and their presence can not be explained without further sampling or exposures on-site.

A commercial color match was provided for both the current aged and darkened appearance of the first-generation paints on the cornice and door architrave and for the appearance of the first-generation paints on the cornice and door architrave after three weeks of light bleaching, which reduced the yellow tone of the original paints. A commercial color match was also provided for a fresh lead white in linseed oil paint. Any of the colors could be used for repainting the trim of the house in the future, but the commercial paint match for fresh lead white in linseed oil paint may be the most consistent with the original appearance of the house. The windows and front doorway have been replaced, but the original paint found on the cornice and rear door architrave can be assumed to have extended to the rest of the trim. The current modern paint color on the house was found to be much darker and slightly more blue than even the aged, degraded first-generation paints. The last several generations of modern paint applied to the trim at the Palmer House have been roughly the same color and are probably based on the "stone gray #271" specified in the 1956 architectural restoration report on this structure.1 It was noted in that report that this was the "usual" paint color. The rear door has been repainted green for the last five generations in a color not dissimilar to the green paints in generation two. This may be evidence of early paint scrapes and color matching or may simply be coincidence.

33The rear door yielded very good early paint evidence that suggests that it was painted more often than the trim, especially in the early life of the house. In generation one and two, red brown finishes were applied, both with primer coats. A good commercial paint match to the dark red-brown paint was provided that can be used for replication on the doors, since presumably the back door was painted to match the now lost front door. During generations three, four, and five the door was bright green with three different finishes being applied, the first with a gray primer. The upper portion of these layers are darker, which may indicate the presence of an oil-rich varnish added to increase gloss. In generation six, the rear door had a decorative finish with an orange primer, yellow base coat, red glaze, and clear varnish. This was probably a faux-graining scheme. This expensive finish was renewed with a second coat of varnish at a later date. In generation eight a second decorative scheme was applied with a cream-colored base coat, a red glaze, and a brown pigmented varnish. This was exposed for long enough that the varnish cracked and collected mold growth. In generation nine, a orange paint and thin varnish were applied. In generation ten, some of the paints on the door contain zinc white which dates them to 1845 or after. This corresponds to the sixth generation of finish on the rest of the woodwork which was painted less often.

The samples taken from the mortar yielded possible evidence of a red limewash under later generations of later paint. The 1956 restoration report noted that the brickwork was cleaned with "steam and paint remover" since the "entire surface had been painted in later years." The painting was likely done in the middle of the nineteenth century to disguise the large wing added to the east end of the house. Some finishes must have been left behind during the 1950s restoration.

Both of the mortar samples also have evidence of a thin, non-fluorescent red layer directly above the mortar that may be a red-pigmented limewash. There is no grime trapped between the mortar and the supposed limewash which suggests that this material was applied soon after the mortar dried. The first thin red layer can not definitively be characterized as a limewash since the fluorochrome stain test for an oil binder was inconclusive and there are few effective scientific methods for definitively identifying a limewash. Scanning electron microscopy with elemental dispersive spectrometry could be used to analyze the supposed limewash. If lead was detected it would suggest that the coating is a paint with a lead white component not a limewash. However, if it is a limewash, a high concentration of calcium should be found in the layer. Furthermore, there is no good way to date the layer since it appears to contain iron oxide red pigment which has been in use for centuries. The evidence from the brickwork therefore can not verify or rule out the possibility of a red limewash having been applied to the Palmer House soon after its construction.

Footnotes

Appendix

Sampling Memorandum

To: Edward Chappell

From: Natasha Loeblich

Re: Sampling at John Palmer House, November 21, 2006

The following is a list of the samples we took from the cornice and mortar of Palmer House today.

| JP1 - | Rear cornice, bottom edge of horizontal bed molding, adjoining lower fascia, below 13th modillion from west end |

| JP2 - | Rear cornice, bed molding, top edge of ovolo, below 12th modillion from west end |

| JP3 - | Rear cornice, bed molding, bottom cyma, lower vertical edge, 3" right of 14th modillion from west end |

| JP4 - | Rear cornice, outer edge of fillet, between cyma and ovolo of bed molding, under 12th modillion from west end |

| JP5 - | Rear cornice, between 13th and 14th modillion from west end, outer, lower edge of fillet, at top of bed molding |

| JP6 - | Rear cornice, outer, lower edge of fillet between cyma and ovolo of bed molding, east of joint between the 15th and 16th modillion from west end |

| JP7 - | Rear cornice, beaded bottom fascia member, just above bead, below 13th modillion from west end |

| JP8 - | Rear cornice, 15th modillion from west end, lower edge of west side, 3" back from front |

| JP9 - | Front cornice, lower edge of 3rd modillion from west end, 4" back from front |

| JP10 - | Front cornice, bottom outer edge of lower cyma on bed molding, below 2nd modillion from west end |

| JP11 - | Front cornice, 2nd modillion from west end, face of fillet on cymatium, 4½" back from front edge |

| JP12 - | Front cornice, upper outer edge of fillet at top of bed molding below 2nd modillion |

| JP13 - | Front cornice, patch of bed molding at west end, middle fillet |

| JP14 - | Rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near middle |

| JP15 - | Rear wall, mortar east of westernmost second-floor window near bottom edge |

Cross-section Preparation Procedures

The samples were initially examined with a stereomicroscope under low power magnification (5 to 50 times magnification) and divided as needed. When possible, a portion of each sample was kept in reserve for future analysis and a portion cast in a labeled cube of a commercial two-part polyester resin manufactured by Excel Technologies, INC. (Enfield, CT). The resin was cured under an incandescent lamp for several hours. The resin cubes were then ground on a motorized grinding wheel with 400 grit sandpaper to reveal the cross-sections. Final finishing was achieved using a Buehler Metaserv 2000 grinder polisher equipped with abrasive cloths from Micro Mesh, INC. with grits of 1500 to 12,000.

Cross-section microscopy analysis was performed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope equipped with an EXFO X-Cite 120 Fluorescence Illumination System fiberoptic halogen light source. The cross-sections were examined at magnifications of 40x, 100x, 200x, and 400x using reflected visible light and a UV-2A fluorescence filter cube with a 330-380nm excitation. The cross-sections were photographed digitally using an integral Spot Flex digital camera with Spot Advanced (v. 4.6) software. The light levels of the images were adjusted in Adobe Photoshop (v. 6.0). The color on the digital images is somewhat indicative of the actual color of the paints, but cannot be used for color matching as the printing process can cause color shifts.

Under ultraviolet light many materials have characteristic autofluorescence colors that can suggest their composition. For example, most natural resin varnishes have a bright whitish autofluorescence while oil varnishes tend to be darker in ultraviolet light. Visible light microscopy can also yield valuable information. The presence of soiling layers or weathering can indicate that the finish layer existed as a presentation surface for a period of time. Since many interior finishes, such as faux graining, make use of a predictable sequence of layers, it is important to determine which layers were meant to be final presentation surfaces.

Binding Media Analysis Procedures

To better understand the composition of the paint binders, selected cross-sections were stained with biological fluorochrome stains to indicate the presence of carbohydrates, proteins, and oils in the paint binders. The stains used were ALEXA (0.1% w/v Alexafluor 488 in dimethylformamide brought to a pH of 9.0 with 0.5% borate) which marks proteins bright green, TTC (4% w/v triphenyl tetrazolium chloride in methanol) which marks carbohydrates dark red-brown, DCF (0.2% w/v 2,7 dichlorofluorescein in ethanol) which marks saturated lipids pink and unsaturated lipids yellow, and TSQ (0.2% w/v N-(6-methyl-8- quinolyl)-p-toluenesulfonamide in ethanol) which marks zinc (Zn2+) blue-white.

Pigment Identification Procedures

Samples with good accumulations of early paints identified through cross-section microscopy were scraped with a scalpel under magnification to reveal the target paint layer. A small amount of this layer was then scraped onto a glass microscope slide, dispersing the pigments. The dispersed pigments were permanently embedded under a cover slip in Cargille Meltmount (Cargille Labs., Cedar Grove, NJ). The Meltmount used has a refractive index of 1.662. The prepared slides were then examined under the microscope with transmitted visible light using a polarizing filter at a magnification of 1000x with an oil immersion objective. The morphological and optical properties of the pigment particles was observed and compared to reference pigment samples.

Color Measurement Procedures

Color measurements were made using uncast samples that were selected under magnification. An effort was made to find a clean, unweathered areas for measurement whenever possible. All color measurements were made using a Minolta Chromameter CR-241 with a measurement area of 0.3mm for uncast samples and a measurement area of 1.8mm for paint swatches. This microscope has an internal, 360° pulsed xenon arc lamp and can measure color with five color systems. The color systems used in this report are the CIE (Commission International de l'Eclairage) L*a*b* and the Munsell color system. Both systems use three values called tristimulus values to measure each color which include hue (or color), the chroma (or saturation), and lightness to darkness. In the CIE L*a*b* color system L* represents lightness from 1 to 100 with 100 being the lightest, a* represents red to green with positive numbers being more red and negative numbers more green, and b* represents yellow to blue with positive numbers being more yellow and negative numbers more blue. This system was adjusted from the CIE Yxy system developed in 1931 to better represent the human eye's sensitivity to color. In the Munsell system, color measurements are given in the form of hue value/chroma with value representing lightness to darkness. Color measurement values are compared to each other using the ΔE formula which calculates the difference between to color measurements.1 The ΔE formula equals the square root of the sum of the differences in the L* value squared, the differences in the a* value squared, and the differences in the b* value squared. Generally, a ΔE value of less than two represents colors that are difficult for the human eye to differentiate.

Commercial color matches were found using swatches from Benjamin Moore and Sherwin Williams. The swatches were compared to the uncast sample under magnification. The best visual matches were then measured to generate a ΔE value.

Palmer House Door Architrave

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP17 | 75.15 | 1.93 | 21.98 | 4.28 | |

| JP17 | 71.82 | 0.76 | 19.17 | 2.98 | |

| JP17 | 74.80 | -0.23 | 17.93 | 0.66 | best match to average |

| JP17 | 73.74 | 0.01 | 16.23 | 2.02 | |

| JP17 | 73.69 | -0.32 | 18.45 | 1.18 | |

| JP16 | 74.33 | -0.25 | 17.17 | 1.10 | |

| JP16 | 79.46 | -0.20 | 16.08 | 5.32 | |

| JP16 | 73.29 | 1.16 | 18.76 | 1.65 | |

| JP16 | 74.70 | 0.50 | 16.62 | 1.44 | |

| Standard Average | 74.55 | 0.37 | 18.04 | ||

| Average of all JP17 | 73.84 | 0.43 | 18.75 | ||

| Average of all JP16 | 75.45 | 0.30 | 17.16 | 2.27 | ΔE of JP16 & JP17 averages |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current paint color | 57.98 | -0.75 | 16.08 | 16.73 | 16.93 | |

| Cornice paint color | 73.29 | -1.15 | 12.53 | 5.86 | 5.68 | |

| SW 6142 | 76.37 | -0.19 | 17.43 | 2.00 | 1.65 | best commercial paint match |

| SW 0011 | 76.42 | -1.39 | 17.69 | 2.59 | 2.01 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 4.30 | 4.16 | |

| BM HC 92 | 76.71 | 0.08 | 16.84 | 2.49 | 2.22 | |

| SW 6157 | 72.91 | -1.34 | 17.46 | 2.44 | 2.24 | |

| SW DCR 003 | 74.95 | 0.58 | 15.76 | 2.33 | 2.32 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP17 | 77.96 | 1.17 | 15.76 | 3.18 | |

| JP17 | 76.78 | 0.04 | 13.71 | 0.69 | best match to average |

| JP17 | 74.91 | -0.04 | 11.58 | 2.22 | |

| JP17 | 74.81 | -0.06 | 14.58 | 2.28 | |

| JP16 | 75.86 | -0.73 | 11.46 | 1.99 | |

| JP16 | 74.63 | 1.21 | 14.18 | 2.40 | |

| JP16 | 76.55 | -0.10 | 12.09 | 1.05 | |

| JP16 | 80.67 | 0.16 | 11.36 | 4.50 | |

| Standard Average | 76.52 | 0.21 | 13.09 | 5.33 | Difference after light bleaching |

| Average of all JP17 | 76.12 | 0.28 | 13.91 | ||

| Average of all JP16 | 76.93 | 0.14 | 12.27 | 1.83 | ΔE of JP16 & JP17 averages |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current paint color | 57.98 | -0.75 | 16.08 | 18.81 | 18.97 | |

| Cornice paint color | 74.33 | -0.55 | 8.77 | 3.60 | 3.16 | |

| BM HC 80 | 76.88 | -0.04 | 13.35 | 0.51 | 0.38 | best commercial paint match |

| SW 2822 | 77.42 | -0.54 | 13.42 | 1.21 | 0.91 | |

| SW 6149 | 76.97 | -0.94 | 13.15 | 1.23 | 1.14 | |

| PP 414-4 | 75.79 | 0.17 | 14.70 | 1.77 | 1.41 | |

| SW 2066 | 78.76 | 0.01 | 12.92 | 2.25 | 2.13 | |

| BM HC 45 | 78.30 | 0.83 | 15.04 | 2.71 | 2.17 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 2.25 | 2.36 | |

| SW DCL 033 | 75.57 | -0.28 | 11.63 | 1.81 | 2.43 | |

| PP 415-4 | 74.74 | 1.19 | 13.04 | 2.04 | 2.44 | |

| SW 2058 | 74.35 | -0.03 | 13.93 | 2.34 | 2.44 | |

| SW 6156 | 77.77 | -1.58 | 15.29 | 3.10 | 2.47 | |

| SW DCR 003 | 74.95 | 0.58 | 15.76 | 3.12 | 2.80 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP17 | 71.95 | -0.29 | 13.50 | 3.82 | |

| JP17 | 77.03 | -0.15 | 12.90 | 1.70 | |

| JP17 | 74.90 | 0.17 | 11.79 | 0.74 | best match to average |

| JP17 | 75.51 | -0.48 | 13.82 | 1.73 | |

| JP17 | 74.77 | -0.44 | 10.59 | 1.76 | |

| JP16 | 76.40 | -0.15 | 11.08 | 1.39 | |

| JP16 | 76.91 | -0.06 | 11.63 | 1.49 | |

| JP16 | 77.03 | 0.12 | 11.11 | 1.84 | |

| JP16 | 75.10 | 0.77 | 12.83 | 1.15 | |

| Standard Average | 75.51 | -0.06 | 12.14 | 6.00 | Difference after light bleaching |

| Average of all JP17 | 74.85 | -0.19 | 13.00 | ||

| Average of all JP16 | 76.36 | 0.17 | 11.66 | 2.05 | ΔE of JP16 & JP17 averages |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ? from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current paint color | 57.98 | -0.75 | 16.08 | 17.98 | 17.48 | |

| Cornice paint color | 74.33 | -0.55 | 8.77 | 3.60 | 3.16 | |

| BM HC 80 | 76.88 | -0.04 | 13.35 | 1.83 | 2.53 | |

| SW 2822 | 77.42 | -0.54 | 13.42 | 2.35 | 3.08 | |

| SW 6149 | 76.97 | -0.94 | 13.15 | 1.98 | 2.71 | |

| PP 414-4 | 75.79 | 0.17 | 14.70 | 2.59 | 3.04 | |

| SW DCL 033 | 75.57 | -0.28 | 11.63 | 0.56 | 0.82 | best commercial paint match |

| PP 415-4 | 74.74 | 1.19 | 13.04 | 1.72 | 1.62 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 1.98 | 2.10 | |

| SW 2058 | 74.35 | -0.03 | 13.93 | 2.13 | 2.22 |

Palmer House Cornice

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP4a | 73.45 | -0.72 | 11.54 | 1.00 | |

| JP4a | 73.29 | -1.15 | 12.53 | 0.38 | best match to average |

| JP4a | 71.74 | -0.52 | 12.18 | 1.51 | |

| JP4b | 74.16 | -0.59 | 10.93 | 1.85 | |

| JP4b | 73.94 | -0.99 | 11.85 | 1.01 | |

| JP4b | 73.52 | -0.86 | 13.13 | 0.72 | |

| JP10a | 73.83 | -0.79 | 11.66 | 1.06 | |

| JP10a | 73.22 | -0.95 | 14.15 | 1.66 | |

| JP10a | 73.21 | -0.52 | 15.21 | 2.72 | |

| JP10b | 73.64 | -1.07 | 10.19 | 2.37 | |

| JP10b | 72.28 | -0.91 | 14.82 | 2.50 | |

| JP10b | 71.98 | -0.32 | 11.79 | 1.48 | |

| Standard Average | 73.19 | -0.78 | 12.50 | ||

| Average of all JP4 | 73.35 | -0.805 | 12.03 | ||

| Average of all JP10 | 73.03 | -0.76 | 12.97 | 1.00 | ΔE of JP4 & JP10 averages |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current paint color | 57.98 | -0.75 | 16.08 | 15.62 | 15.72 | |

| Door architrave pt | 74.80 | -0.23 | 17.93 | 5.69 | 5.68 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 1.87 | 1.91 | |

| SW 2058 | 74.35 | -0.03 | 13.93 | 1.99 | 2.08 | |

| SW 2072 | 70.81 | -0.02 | 12.97 | 2.54 | 2.76 | |

| BM HC 82 | 73.22 | -0.47 | 14.82 | 2.34 | 2.39 | |

| PP 415-4 | 74.74 | 1.19 | 13.04 | 2.57 | 2.80 | |

| BM HC 95 | 70.78 | -0.68 | 14.01 | 2.85 | 2.95 | |

| SW 6150 | 71.65 | -0.48 | 13.22 | 1.73 | 1.90 | best commercial paint match |

| SW DCL 003 | 75.57 | -0.28 | 11.63 | 2.58 | 2.60 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP4a | 72.58 | -1.42 | 8.70 | 1.41 | |

| JP4a | 72.86 | -1.92 | 8.29 | 1.57 | |

| JP4a | 71.66 | -0.94 | 9.35 | 2.26 | |

| JP4b | 74.50 | -0.47 | 8.21 | 1.02 | |

| JP4b | 74.33 | -0.55 | 8.77 | 0.59 | best match to average |

| JP4b | 73.71 | -1.23 | 9.49 | 0.70 | |

| JP10a | 74.89 | -0.76 | 6.65 | 2.47 | |

| JP10a | 75.50 | -0.67 | 6.50 | 2.91 | |

| JP10a | 72.72 | -0.10 | 8.13 | 1.59 | |

| JP10b | 75.04 | -0.89 | 11.49 | 2.85 | |

| JP10b | 76.17 | -1.05 | 10.24 | 2.67 | |

| JP10b | 72.48 | -0.67 | 10.94 | 2.48 | |

| Standard Average | 73.87 | -0.89 | 8.90 | 3.67 | Difference before and after light bleaching |

| Average of all JP4 | 73.27 | -1.09 | 8.80 | ||

| Average of all JP10 | 74.47 | -0.69 | 8.99 | 1.27 | ΔE of JP4 & JP10 averages |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current paint color | 57.98 | -0.75 | 16.08 | 17.44 | 17.91 | |

| Door architrave pt | 74.90 | 0.17 | 11.79 | 3.25 | 3.16 | |

| SW 2065 | 74.44 | -0.28 | 13.79 | 4.96 | 5.03 | |

| SW 2058 | 74.35 | -0.03 | 13.93 | 5.13 | 5.19 | |

| SW 2072 | 70.81 | -0.02 | 12.97 | 5.17 | 5.51 | |

| BM HC 82 | 73.22 | -0.47 | 14.82 | 5.97 | 6.15 | |

| PP 415-4 | 74.74 | 1.19 | 13.04 | 4.72 | 4.63 | |

| BM HC 95 | 70.78 | -0.68 | 14.01 | 5.98 | 6.33 | |

| SW DMV 120 | 75.51 | -1.97 | 9.68 | 2.11 | 2.06 | best commercial paint match |

| SW DCL 003 | 75.57 | -0.28 | 11.63 | 3.28 | 3.13 | |

| SW DMV 103 | 71.07 | -0.53 | 9.77 | 2.95 | 3.41 | |

| SW 2073 | 77.90 | -0.10 | 10.54 | 4.42 | 4.01 |

Palmer House Door

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP18 | 28.70 | 2.15 | 5.65 | 2.31 | |

| JP18 | 25.40 | 4.14 | 6.06 | 2.65 | |

| JP18 | 26.63 | 4.76 | 5.81 | 1.61 | |

| JP18 | 28.90 | 5.29 | 6.58 | 1.40 | |

| JP18 | 27.81 | 3.89 | 6.58 | 0.42 | best match to average |

| JP18 | 30.69 | 5.07 | 7.81 | 3.13 | |

| Standard Average | 28.02 | 4.22 | 6.42 |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW 2021 | 30.19 | 5.04 | 5.52 | 2.49 | 2.85 | |

| SW CW 120 | 30.45 | 4.97 | 5.13 | 2.85 | 3.20 | |

| SW 6006 | 25.94 | 5.01 | 3.70 | 3.51 | 3.61 | |

| BM 2134-10 | 30.19 | 2.30 | 4.24 | 3.62 | 3.70 | |

| SW 2035 | 30.93 | 2.72 | 4.83 | 3.63 | 3.76 | |

| BM 2115-10 | 28.48 | 3.53 | 5.92 | 0.96 | 1.01 | best commercial paint match |

| BM 2111-10 | 27.68 | 2.52 | 4.86 | 2.33 | 2.20 | |

| BM 2021 | 30.19 | 5.04 | 5.52 | 2.49 | 2.85 | |

| BM 2116-10 | 27.05 | 3.10 | 3.91 | 2.91 | 2.89 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔE from average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JP18 | 30.25 | 3.05 | 5.20 | 2.29 | |

| JP18 | 25.74 | 4.07 | 5.38 | 2.72 | |

| JP18 | 25.88 | 4.77 | 5.81 | 2.60 | |

| JP18 | 27.95 | 4.45 | 6.22 | 0.60 | best match to average |

| JP18 | 32.11 | 4.14 | 7.50 | 4.01 | |

| Standard Average | 28.39 | 4.10 | 6.02 | 0.55 | Difference after light bleaching |

| Color Matches | ΔE from average | ΔE from best match to average | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SW | 2021 | 30.19 | 5.04 | 5.52 | 2.10 | 2.42 | |

| SW CW 120 | 30.45 | 4.97 | 5.13 | 2.41 | 2.78 | ||

| SW 6006 | 25.94 | 5.01 | 3.70 | 3.49 | 3.27 | ||

| BM 2134-10 | 30.19 | 2.30 | 4.24 | 3.11 | 3.68 | ||

| SW 2035 | 30.93 | 2.72 | 4.83 | 3.13 | 3.72 | ||

| BM 2115-10 | 28.48 | 3.53 | 5.92 | 0.58 | 1.10 | best commercial paint match | |

| BM 2111-10 | 27.68 | 2.52 | 4.86 | 2.08 | 2.38 | ||

| BM 2021 | 30.19 | 5.04 | 5.52 | 2.10 | 2.42 | ||

| BM 2116-10 | 27.05 | 3.10 | 3.91 | 2.69 | 2.82 |